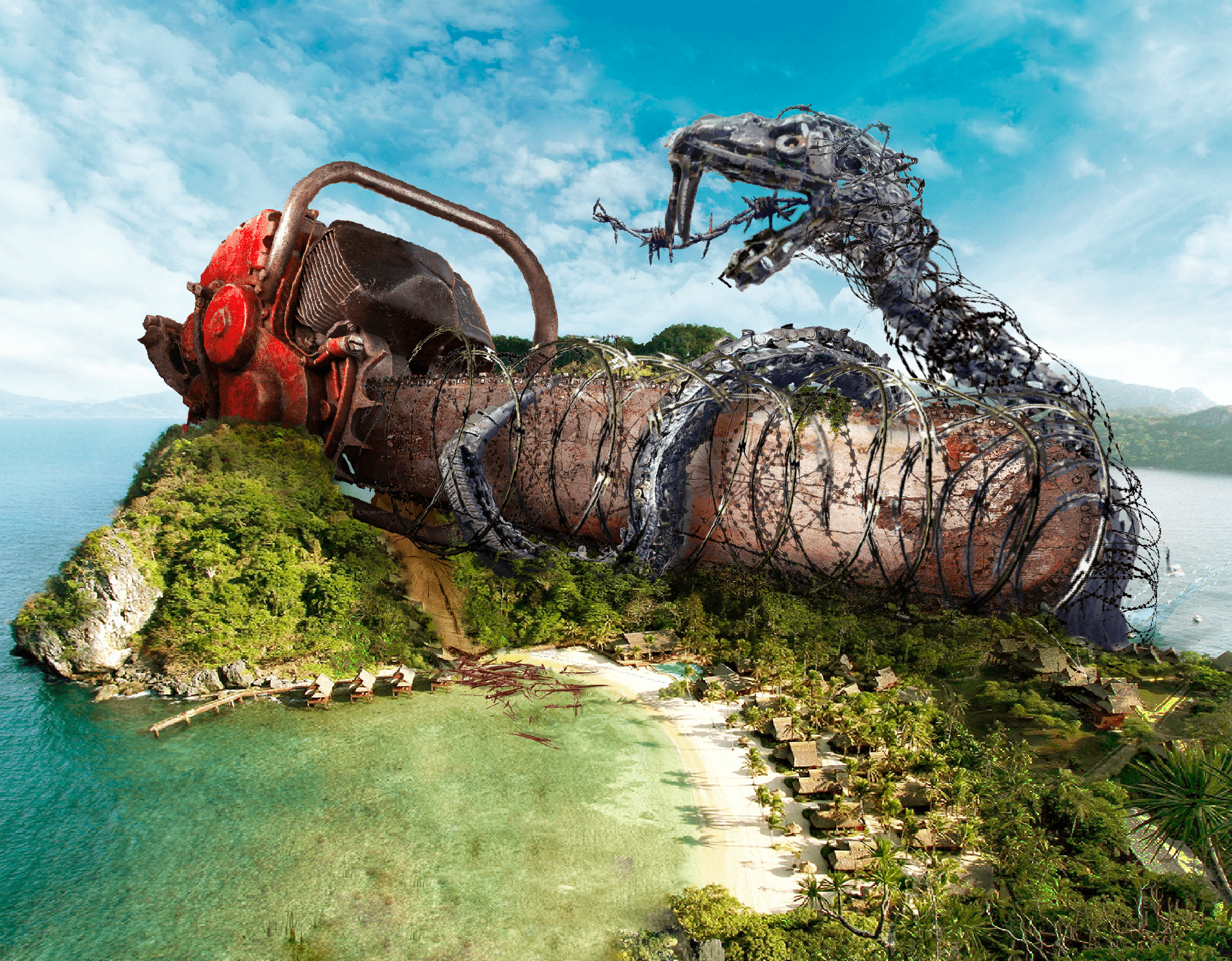

The Marcos Jr. administration’s push for supposedly green programs lies in stark contrast with continuing environmental degradation and development aggression linked to negligent agencies and profiteering corporations, said environmental advocates during the Center for Environmental and Concerns’s State of the Philippine Environment 2025 forum.

Policies such as the National Greening Program, a reforesting initiative first introduced in 2011 to combat deforestation, remain a stated priority for the Marcos Jr. administration. However, major deforestation events occurred on as many as one in 25 hectares of the program’s land, while native trees are often uprooted in favor of invasive species such as mahogany.

A 2019 Commission on Audit review also found that only 13.92% of new trees planted under the program survived and that P2.8 billion in the program budget remained underutilized for the first eight years.

Yet the program has failed to address deforestation brought about by infrastructure projects such as Ahunan Dam, to be operated in part by billionaire Enrique Razon’s Prime Infrastructure Inc.

“Patuloy na pinagkakait ang yaman, lupa, at karapatan sa ordinaryong Pilipino habang nagkukubli ang mga pamilyang nagkakamal ng kita,” said CEC Research and Advocacy Coordinator Joice Leray during her forum segment.

Meanwhile, the administration’s renewable energy thrust is top-down and underfunded, with a focus on costly transition fuels such as imported liquefied natural gas, the panelists contended. Its renewable projects often trespass onto indigenous land, as in the case of Kaliwa Dam—expected to submerge 93 hectares of forest and threaten 100,000 residents with heavy flooding.

Despite a 2023 verbal order to suspend reclamation projects pending review from the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR), the palace has issued no official, written proclamation on the halt. A DENR cumulative impact assessment in April found that Manila Bay reclamation could trap pollutants in water and devastate fishing grounds, while the Philippine Reclamation Authority drew flak in May for the proposed uprooting of mangroves at the Las Piñas-Parañaque Wetland Park to make way for reclamation.

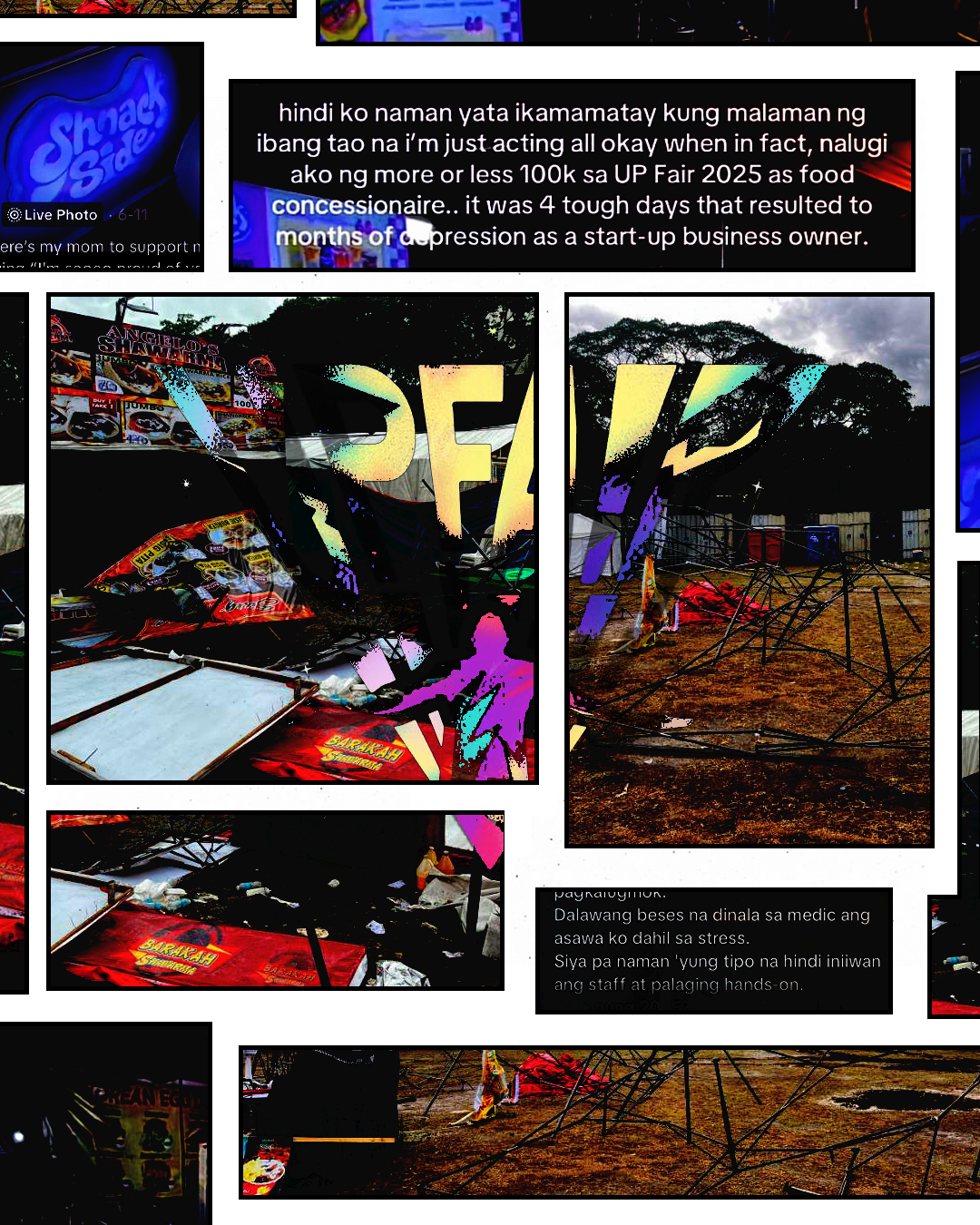

Navotas fisherman Aaron Escarial narrated the profit motive behind reclamation and demolitions in the area during the panel discussion, where thousands of small fisherfolk livelihoods remain at risk. “Napakaganda pakinggan ang development projects, pero maraming matatamaan na mangingisdang Pilipino, at ang sistema dapat hindi mala-dayuhan na paaalisin kami at kuhanan ng karapatan na makapag-hanapbuhay,” he said.

Corporations also often undertake behemoth mining projects, to the detriment of local communities. San Miguel Corporation is now also operating a 17,000-hectare stretch of coal mining contracts in South Cotabato and Sultan Kudarat, long opposed by T’boli and Manobo advocates. Large-scale mining is also rife with safety concerns: A Davao de Oro quarry of Razon-owned Apex Mining Corporation was befallen by a landslide that killed 98 residents and employees.

Environmental advocates oppose such corporate control, counterposing small-scale, community-based renewable energy projects as an alternative to large-scale mining and energy projects.

Yet, physical and legal threats to advocates’ safety continue. From 2012 to 2023, 298 land and environmental defenders were killed in the Philippines, according to a count by Global Witness. As a result, the Philippines remains the most dangerous in Asia for environmental advocates.

Groups cited the case of Oriental Mindoro, where residential areas were bombed in military offensives linked to mining ventures of a subsidiary of DMCI Holdings and where Iraya Mangyan farmers on Hacienda Almeda were similarly isolated and harassed last year. Recently, guards tied to San Miguel have been harassing indigenous residents and fisherfolk of Bugsuk, Palawan and intruding on their land.

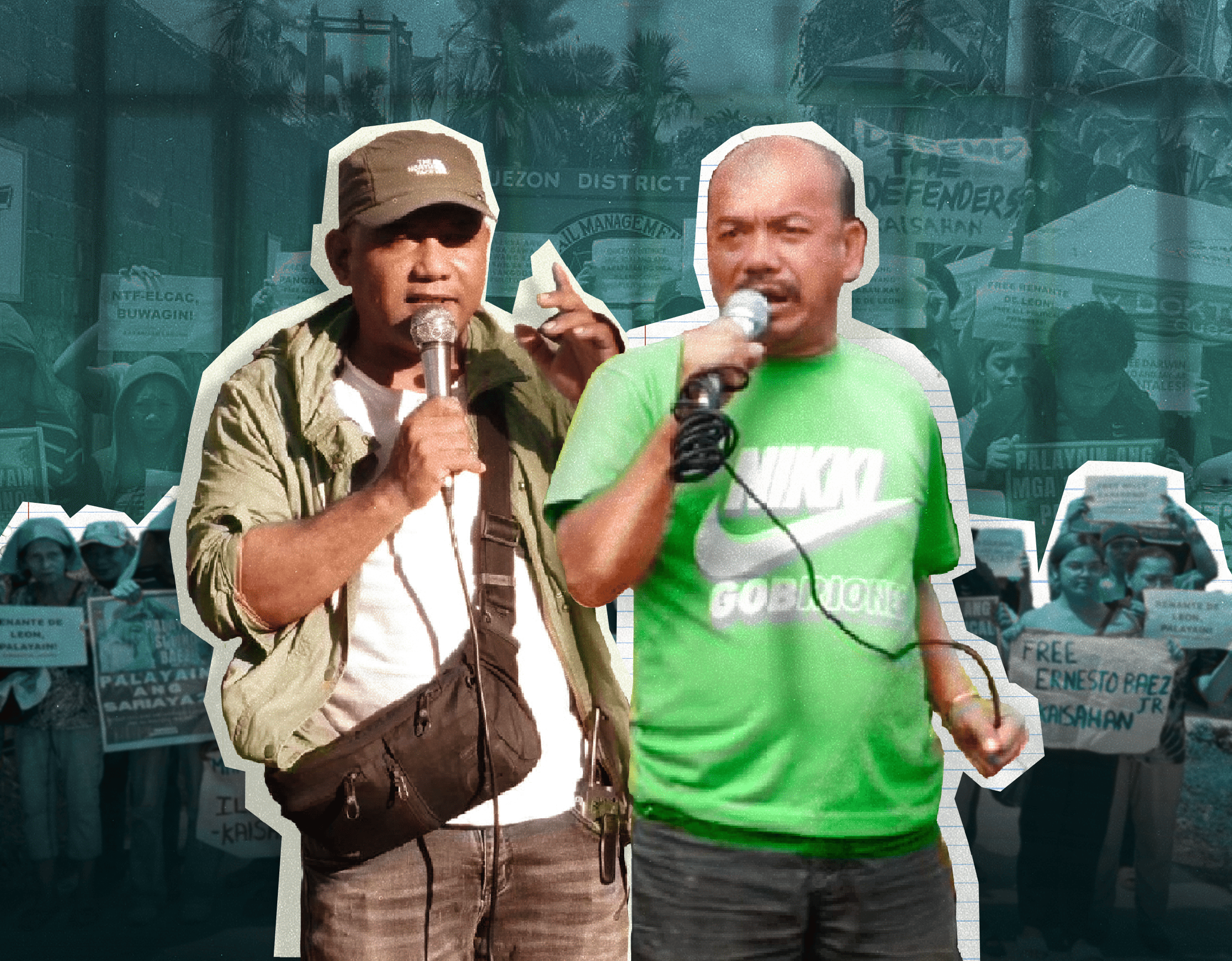

Aside from outright force, state and private actors weaponize the law, the forum panel said, as with landowners in Sumalo, Bataan, who filed more than 50 cases against farmers struggling for land. Raven Desposado of youth organization TAKDER described a similar pattern in the terrorist designations of leaders of the Cordillera Peoples Alliance through the Anti-Terror Act.

The groups asserted that a discernible pattern of state harassment by legal means has emerged: “Dismiss, sampa, dismiss, sampa,” described journalist Inday Espina-Varona during the forum’s panel segment.

Yet amid intense red-tagging and harassment, advocates and sectors pledged to stand firm against the continued intrusion of state forces and private security onto indigenous and other protected lands.

“Hindi dapat tayo kumikilos sa limitasyon na takot tayong ma-red-tag. Totoong maraming pinapatay dahil sa red-tagging, pero kolektibo nating labanan ang red-tagging, dahil unconstitutional naman yan,” said Eloisa Mesina of Katribu during the forum. ●