“Parang Luneta na lang ang UP ngayon,” an anonymous user lamented on r/peyups. It’s a sentiment grounded in the hum of cars congesting the oval, in hawkers selling taho and turon by the Sunken Garden benches, and in joggers and cyclists who come and go. With the influx of “outsiders,” the university feels like it belongs to everyone and no one at the same time.

As a public university, UP is meant to serve the people and function as an open, democratic space. But that space is increasingly becoming too stretched and too cramped. The campus no longer breathes freely, with the already few org tambayans commercially repurposed, facilities and roads closed off for paid events, and the absence of dedicated faculty spaces.

As space shrinks, acts of gatekeeping emerge from the UP community. When someone complains that they can no longer enjoy the peace at Sunken Garden because it is chaotically crowded by outsiders, they are effectively saying that they have a greater right to that space. But this exclusionary tendency is a symptom of the national government’s neglect of public spaces, and the UP admin’s role in tightening its grip on the few that remain.

UP for All

Conceived with public purpose, UP has stood as more than just an institution of learning. It has become a haven for displaced communities and refugees, and a bastion of non-conformist resistance. The university resisted the Committee on Anti-Filipino Activities’s witch hunts in the 1960s, lobbied alternative UP charters seeking a more pro-people institution in the early 2000s, and welcomed Palestinian refugees in 2023.

This tradition of openness is not only ideological but also spatial. UP stands as a rare retreat in a city starved of public spaces. While the Acad Oval was not originally conceptualized as a public park from the outset, per Ateneo de Manila University researchers Czarina Saloma and Erik Akpedonu, it nonetheless developed into one, shaped by necessity and sustained by the university’s openness to the wider public. Yet, while UP continues to allow the presence of the masses, recent policies have increasingly restricted this access.

While areas like the Acad Oval and Sunken Garden continue to attract a diverse crowd, incidents such as the displacement of informal settler families in Pook Aguinaldo and Pook Arboretum, the forced clearing of vendors, and the sudden demolition of the campus guards’ encampment shed light on how the UP administration is quietly remolding the campus, once anchored in the presence of the masses—workers, vendors, students, and staff—through actions of exclusion that reshape the terms of their access.

UP for Grabs

Public spaces play a vital role in maintaining urban order, serving political, social, and economic functions within the city. They are not just physical areas, but spaces of potential, functioning as dynamic spaces that meet a variety of needs.

Public spaces serve as a refuge from forms of separation based on class, race, ethnicity, and gender. These spaces are avenues where individuals from all walks of life cross paths, explains sociologist Stéphane Tonnelat. In UP, this dynamic comes to life in simple interactions, like when students bring their friends to visit or when students and marginalized groups gather for rallies. These encounters contest the idea that the UP community is an exclusive one.

People confront and revise their own preconceived notions against diverse groups of society when they encounter them in public spaces, Tonnelat adds. In events like mobilizations, the UP community is exposed to perspectives that disrupt dominant narratives. In the same way, outsiders see that the university is not a walled community—a realization of the ideals of openness and inclusivity on which UP has been historically nurtured.

UP for the Few

The frustration over spaces stretched too thin points to a deeper issue: a growing scarcity of areas once meant for the collective. Even in places like UP, where public use once felt more possible, access is shrinking. Facilities are left unfinished, libraries are guarded by ID checks, and cars have reclaimed the oval. As this slow erosion goes unchecked, people begin to turn on one another, targeting others only seeking places where they can fit in.

This dynamic corresponds to Deleuze and Guattari’s concept of microfascism, which holds that fascist tendencies exist in all members of society. Under such a concept, fascism is not just imposed from above but also from below. Central to microfascism is a desire for power, order, and organization that operates subtly and invisibly, circulating through everyday interactions.

Deleuze and Guattari critique the ways people internalize and reproduce oppressive structures in small but pervasive ways. Although not always overt or violent, and however petty such desires may seem, these microfascist behaviors sometimes stem from the socially produced desire for regulation and order, rather than ignorance.

In UP, microfascism further reveals itself in irritation at passersby, joggers, families, and tourists, dismissed as outsiders. While the UP community sounds no official calls to gate the university’s spaces, the notion that having too many people on campus is problematic hints at a growing sentiment that could give rise to microfascist tendencies, possibly even escalating to an overt fascist one, as Deleuze and Guattari would suggest.

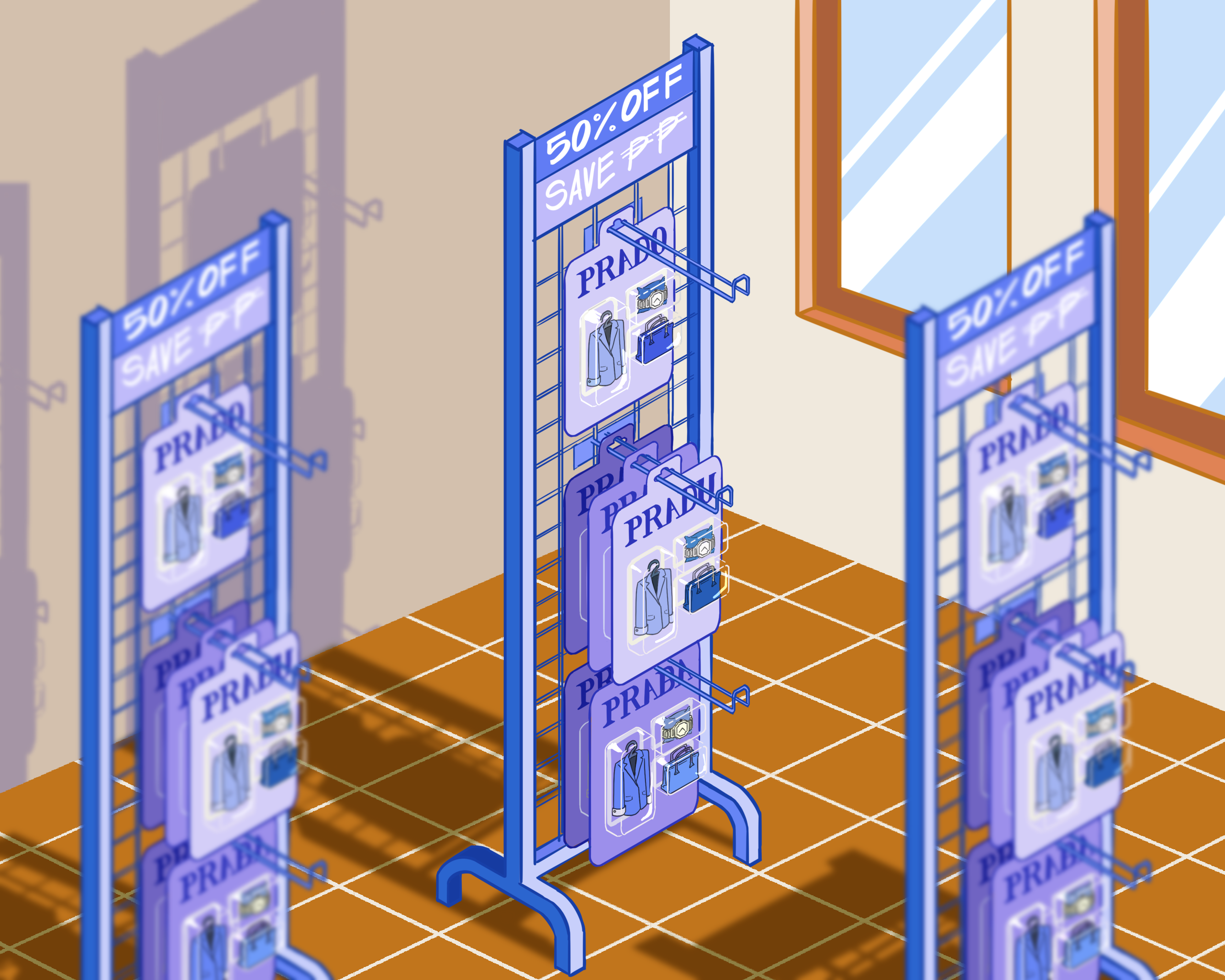

In parallel, the UP admin’s questionable actions, ranging from prioritizing institutional precedents over addressing labor precarity and the skewed prioritization of commercial buildings versus the needs of the university, signal a fascist tendency in the institution to regulate rather than share space. These actions reflect the administration's warped vision of UP as a profit-driven institution, diluting the university’s historical public character.

This leaves the UP community at a crossroads, as the public character of the university’s grounds becomes contested. It appears easier to mistake the “outsiders” as the problem, when in reality, it is the joint complicity of the national government and the UP administration—in failing to uphold commitments to public spaces and in betraying the university’s mandate—that spawns this confrontation.

For students, the challenge is to reimagine how they take up space, not only physically but also politically and collectively. And in taking up space, the goal is not merely to defend our place in the university, but instead to foster a space that includes. This entails supporting vendors’ livelihoods, clamoring for open facilities to the public, and resisting policies that fence people off campus.

Being part of the UP community should mean more than just occupying its grounds: It means fostering an environment that allocates spaces for those who need them. In honoring the historical public character of the university, there is a need to strive to keep it open and responsive to those who will seek refuge within, not only for the few but for the countless voices yearning for the space UP has always promised to be. ●

First published in the May 7, 2025, print edition of the Collegian.