In the last three months, the coastlines of Sitio Marihangin in Palawan have been filled with rows of camping indigenous Molbog, including elders and children, who sleep in their makeshift tents to deter the entry of armed personnel who harass, open fire, and intrude on the island. Such life has become normal for a people long persecuted for defending their ancestral lands against San Miguel Corporation (SMC) and pearl jewelry firm Jewelmer Corporation.

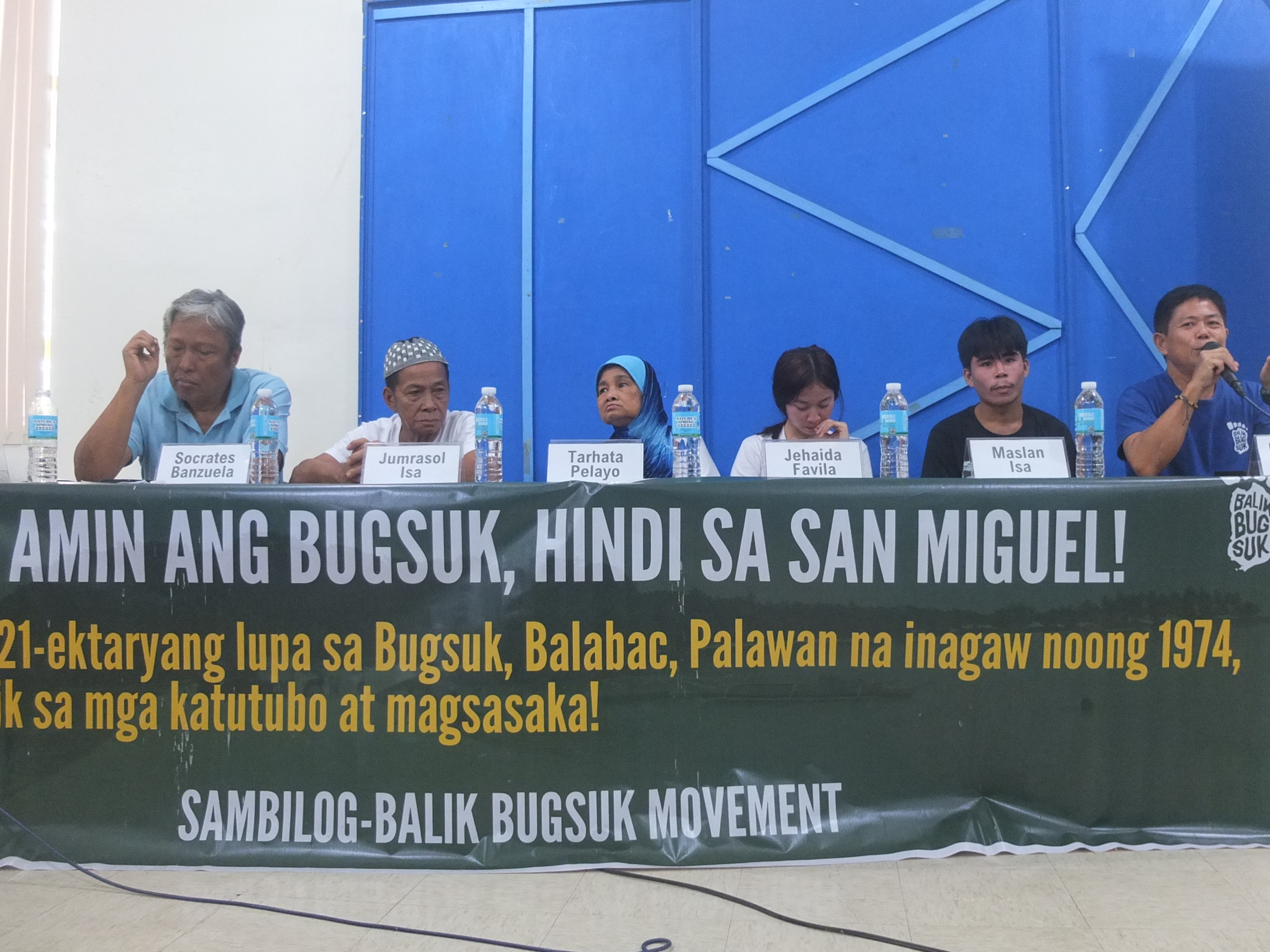

Socrates Banzuela, a legal figure of the Pambansang Kilusan ng mga Samahang Magsasaka, talks to residents of Sitio Marihangin on their makeshift tents in the coastline of their island. (PAKISAMA)

Socrates Banzuela, a legal figure of the Pambansang Kilusan ng mga Samahang Magsasaka, talks to residents of Sitio Marihangin on their makeshift tents in the coastline of their island. (PAKISAMA)

Heightening tensions ensued after the arrest of Oscar Pelayo Sr., a 69-year-old Molbog figurehead from Sitio Marihangin on May 17, days after several protestors known as the Mariahangin 10 were also detained. SMC has been pushing for the removal of native Molbog for its luxury ecotourism project in Bugsuk.

For decades, indigenous groups have been subjected to corporation-driven brutality and divisive tactics. Such struggles of the Molbog, who banded together as the SAMBILOG Balik Bugsuk Movement (SBBM), are compounded by the government’s complicit silence.

How Did This Issue Unfold?

The Balabac isles, located in the southwestern extremes of the country, are home to several indigenous people (IP) communities. Some of its portions are occupied by Jewelmer and SMC.

Instances of land-grabbing in the region date back to the 1974 displacement of Molbog and Palaw’an families in a 9,915-hectare territory in Balabac by Danding Cojuangco for a coconut farm. Not long after, in 1981, 8,338 hectares of fishing grounds were seized to make room for Jewelmer’s pearl farm, co-owned by Danding’s brother, Manuel Cojuangco.

Indigenous resistance soon mounted on the islands’ beachfronts. SAMBILOG, a group of Molbog, Cagayanen, and Palaw’an families in Balabac, was established in 1998. The group applied for Certificate of Ancestral Domain Titles (CADT) in 1999 and 2005 for portions of Mariahangin Island, Sibaring, and Tagnato.

In 2000, the applications from the previous year were approved, but issuance was stifled due to the turbulent transitory period of then President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo. They also applied for a Notice of Coverage, which allowed the group to reacquire 10,713 hectares of private land upon its approval in 2013, though it was revoked a decade later.

Following the revocation, plans to pursue the ecotourism project ensued. After Danding sold most of his shares in SMC to Ramon Ang in 2012, Ang sought to diversify SMC. As a result, the 5,567-hectare ecotourism project, occupying most of Bugsuk Island, was formally declared in its 2023 report to the Securities and Exchange Commission.

As many as 41 to 80 masked blue guards from JMV Services, said to be likely hired by SMC, have intruded on the island in May and April this year. The guards used batons and even firearms to make the residents leave.

As a result, some residents have chosen to flee. As many as 30 families left the island, according to a Bulatlat report. Some, who chose to stay and fight, have fallen victim to trumped-up grave coercion charges.

These charges, filed by former National Commission on Indigenous Peoples (NCIP) Executive Director Cesar Ortega, were based on a June 2024 incident where the Mariahangin 10 peacefully blocked the Ortega-led group of police personnel and SMC employees from conducting a dialogue in Sitio Marihangin. They feared that Ortega would just bribe the residents once again. The 10 residents were all arrested a year later.

The group needed P36,000 for each member, totaling a P360,000 bail. They are still behind bars at Brooke’s Point District Jail. But Pelayo Sr. has non-bailable illegal fishing charges against him. He is currently detained in Iwahig Penal Farm in Puerto Princesa, some 200 kilometers away from Balabac, leaving him with minimal contact with the SBBM.

Apart from corporations’ harassment tactics, they have also taken advantage of the rifts among the Molbog.

Why is Another Molbog Group Opposing SBBM?

Another group of Molbog emerged as a countermovement to SBBM. The group, led by Ariel Monserapa, the designated Indigenous Peoples Mandatory Representative of Balabac, staged its own set of campaigns in Metro Manila to steer the narrative against SBBM, according to SBBM Chairperson Romillano Calo.

Monserapa is the nephew of Tarhata Pelayo, a supporter of SBBM, underscoring cracks within the community. But some Molbog elders do not consider Monserapa their tribe’s chieftain. Despite this, the Monserapa-led group, SAMAKA, which detracted from SBBM in the early 2000s, was the one invited by NCIP to convene for possible solutions over the island’s ownership.

This group, largely absent from the 2005 CADT discussions, published a letter in December 2024 that sought to undo the support that SBBM has garnered. It tagged SBBM as fake representatives of the Molbog because they have non-Molbog members. They also targeted Calo, who was an indigenous Palaw’an. But Calo and his late father have been leading the organization for more than two decades, and have helped the Molbog in arming a legal defense against SMC.

The companies take advantage of the impoverished economic situations of other Molbog, who may have accepted SMC’s and Jewelmer’s support in exchange for undermining SBBM, according to Calo. This is not the first time corporate forces divided communities: Dissidence against a Hydrometallurgical Processing Plant was curbed through its operating firm’s “divide and rule” strategy in 2002, while some indigenous groups in 2005 were pressured by a nickel mining company to succumb, as shown in a 2012 Communication for Empowerment study.

This is also why once SBBM caught wind in recent years, counteropposition ramped up. “Kaya, nung naka-gain siya (Bugsuk) ng popularity, lumala din yung paglaban ng kabilang pwersa (SMC),” according to former Pambansang Kilusan ng mga Samahang Magsasaka (PAKISAMA) social media manager Angellica Paller.

What Are the Steps Forward?

The Bugsuk launched peaceful means of resistance, such as a seven-day hunger strike in November 2024 in front of the Department of Agrarian Reform (DAR), where they requested a dialogue with DAR Secretary Conrado Estrella III, who did not respond. They also joined a 4,000-kilometer march across the country to rally support for their cause that began in March and ended May 10.

The Molbogs’ actions have raised awareness nationwide. Boycotting SMC, winning over public support from organizations like the Catholic Bishops' Conference of the Philippines, and strengthening grassroots organizations in universities remain relevant steps forward, said Socrates Banzuela, a legal figure in PAKISAMA aiding the SBBM’s struggle. The movement was also able to raise P300,000 in bail money for the Mariahangin 10.

Aside from financial support, there remain many opportunities to forward the movement beyond freeing the jailed protestors. Banzuela noted the legal fronts the Molbog are ready to forward to reclaim Bugsuk Island. The issuance of the Strategic Environment Plan and the Environmental Compliance Certificate from government agencies may be able to block SMC’s continuation of its ecotourism project.

The Molbog have a long fight ahead of them, clashing toe-to-toe with the multibillion conglomerates SMC and Jewelmer. Their ancestors, who have tended much to the ancestral lands of Bugsuk, Mariahangin, and Sibaring, have existed before these corporations, and will exist long after these firms are gone. ●

First published in May 27, 2025, print edition of the Collegian.