By RICHARD CALAYEG CORNELIO & KENNETH GUTLAY

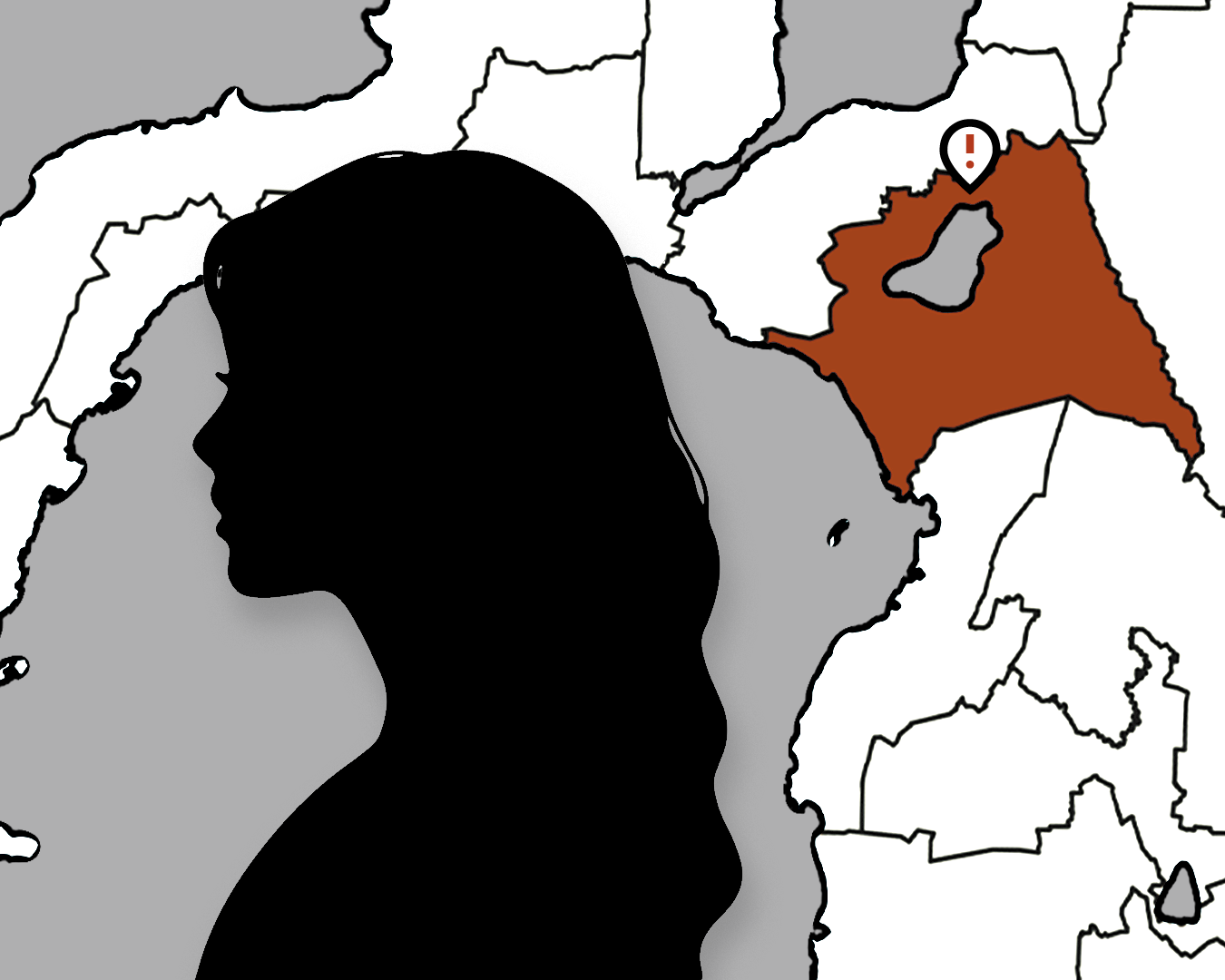

A shower of mortar rained down upon the rooftops as the day's first rays of sunshine raced to the sleepy town of Mapaniqui, Pampanga. When the dust settled, members of the Imperial Japanese Army, 600 soldiers all in all, stormed the village, destroying houses, murdering men, and corralling women to be used as sexual slaves overnight. Lita Vinuya, eight years old that day on November 23, 1944 in the middle of the second world war, was one of them.

More than seven decades have passed. The drums of war have long laid silent. Lola Lita, now 82, recalls the fate she and her sister Emilia, 11 years old at the time, suffered when they were taken as comfort women by Japanese soldiers.

Down Memory Lane

Her father was the teniente del barrio or the barangay captain of Makapilapil, Bulacan where she was originally from. Upon learning that the Japanese were coming, he planned to send his two daughters away to hide in the mountains. He sold the family carabao to buy supplies for his children, but the market was closed. The sisters instead went to Mapaniqui, a mere four kilometers away, to stay with their father's compadre.

Lola Lita recalls sleeping that night and waking up to the sound of bombs.

“Nung lumiliwanag na, panay na ang bagsak ng mortar. Nung huminto ang pagbagsak ng mga mortar na yun, ang Hapon, pinasok na ang barangay,” Lola Lita said.

The men and women were separated into two groups. Houses were looted. Anything of value was taken. The soldiers fired with machine-guns on the men who were bound and tied up.

Their corpses were doused with gasoline, dumped in the school building, and burnt. When every corner of the town was pillaged, everything else was set ablaze, leaving nothing but ash and 37 smoking corpses.

“Matapos, ang mga babae naman ang hinarap nila."

Mothers, daughters, and all the women from Mapaniqui were forced to carry the loot to the infamous Bahay na Pula or Red House which the soldiers used as a garrison.

Owned by Don Ramon Ilusorio, the Red House, a worn-down wooden building that was once a symbol of excess and opulence, now serves as a gravestone for the atrocities committed in its haunted halls. The building was partially demolished in August 2016, and now only the façade and beams remain.

Once there, the Japanese soldiers took turns and forced themselves upon the women. “Kanya-kanyang pwesto, kanya- kanyang lugar,” said Lola Lita.

Other kids like her were not spared as well. “Maraming beses nilang inulit-ulit yung kabastusang yun.” The women were sent back to the smoldering remains of their barangay the next morning. Around a hundred women were left with no homes, no families to return to, with nothing but a bleak future.

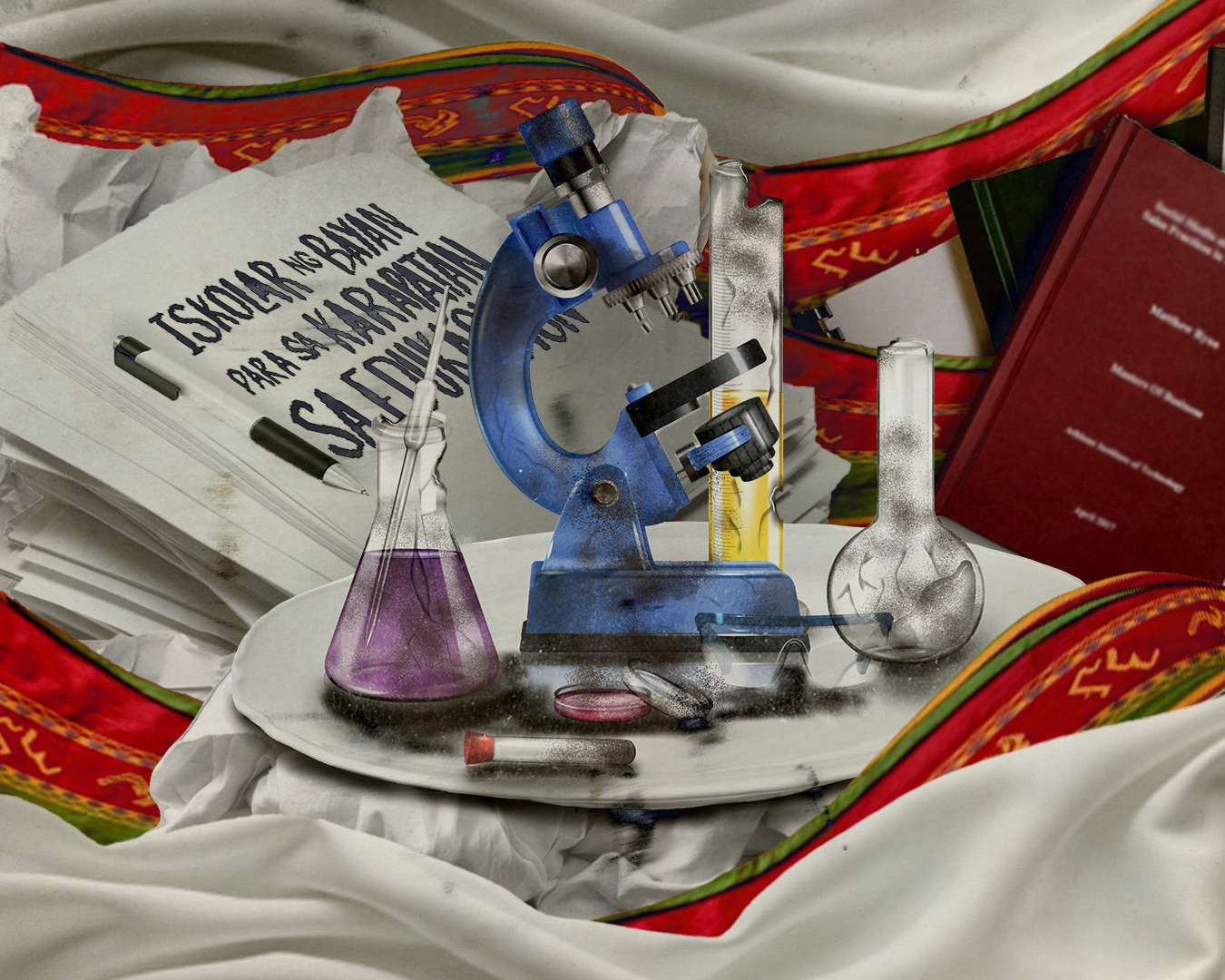

In the 1990s, archives of Japanese war documents disclosed the Imperial Army’s savagery, how they took on more than 200,000 comfort women all over the world during the war. Around a thousand of these were Filipinas rounded up and taken in by force during the Japanese occupation of the country.

In Lola Lita's barangay, only 29 of over 100 victims are still alive. Many are now bedridden, waiting for redress long denied them and other comfort women who did not live to see justice served.

Moving Forward

Recounting the violence inflicted upon them, Lola Lita could not but lament the pointlessness of war-where to be a woman, to be poor, and to be Filipino were to be triply vulnerable to abuse at the hands of the Japanese military. The functional use of comfort women not only sated the male soldiers' craving but motivated them into furthering Japan's militarist and imperial project.

More than internalized feelings of guilt and self-blame, the survivors from Mapaniqui had until the late 1990s opted to blot the fact of their suffering out of village memory, and for a long while even from their husbands and relatives, due to fear that their stories would find no audience. Especially in a country where a woman's worth is still largely predicated on her "purity," their silence for over half a century lends momentum to their act of finally speaking out in 1997.

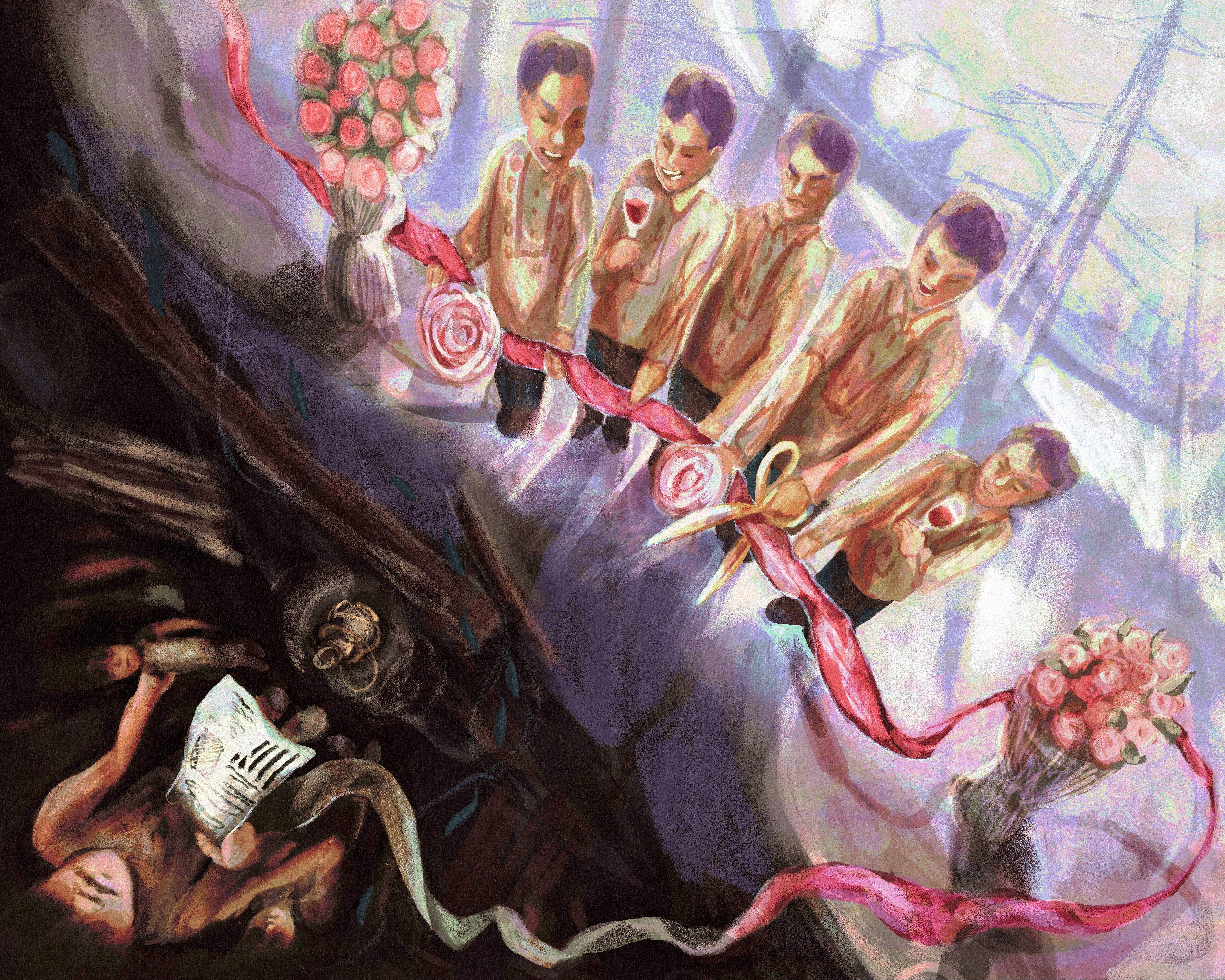

However, more than 20 years since coming forward, Lola Lita and others have yet to receive apologies from the Japanese government and adequate financial compensation for them and their families.

In both international and local courts, their allegations of rape have been met with denialism of the perpetrators. This owes to difficulties of meeting the burden of proof required and other such legalities that tend to waive the state's duty to probe war crimes against the civilian population.

The Philippine government's lukewarm support and its initial whitewash of the entire issue may be attributed to its fear of compromising important Japanese deals and having to renegotiate initial monetary reparations from Japan after wartime. The removal of the comfort women statue in Roxas Boulevard, coincidentally after a Japanese minister expressed displeasure over it, likewise bespeaks the kind of historical revisionism that translates into institutional neglect.

And so, even to this day, the nation's collective memory of the comfort women remains contingent on survivor testimony, with minimal juridical backing and no authoritative admission of the reality of such an atrocity.

For Lola Lita, such an inadequate response from the government and its refusal to act on their legitimate demands are yet another betrayal they could no longer just suffer. "Bakit di nila kami tulungan para bigyan kami ng hustisya, ng ligal na kabayaran?” asked Lola Lita. “Katulad ngayon, iilan na lang kaming buhay."

They worry that the persistence of their struggle would wear out along with the deterioration of their bodies. Their voices may be feeble and their numbers dwindling, but they who have survived violence and inhumanity will go on rallying new voices and warm bodies who will continue their fight and write their narratives of resistance into cultural memory. ●

Published in print in the Collegian’s December 14, 2018 issue, with the headline “Slaves of Destiny: The discomforting narrative of the Philippine ‘comfort women’.” All photos were taken by Jiru Rada.

Exactly 77 years after the Japanese attacked the village of Mapaniqui, Lola Lita succumbed to pneumonia, aged 89. Until her death, the Japanese government has still not recognized the women of Mapaniqui as victims of sexual abuse during the war. No compensation has been given to Lola Lita.