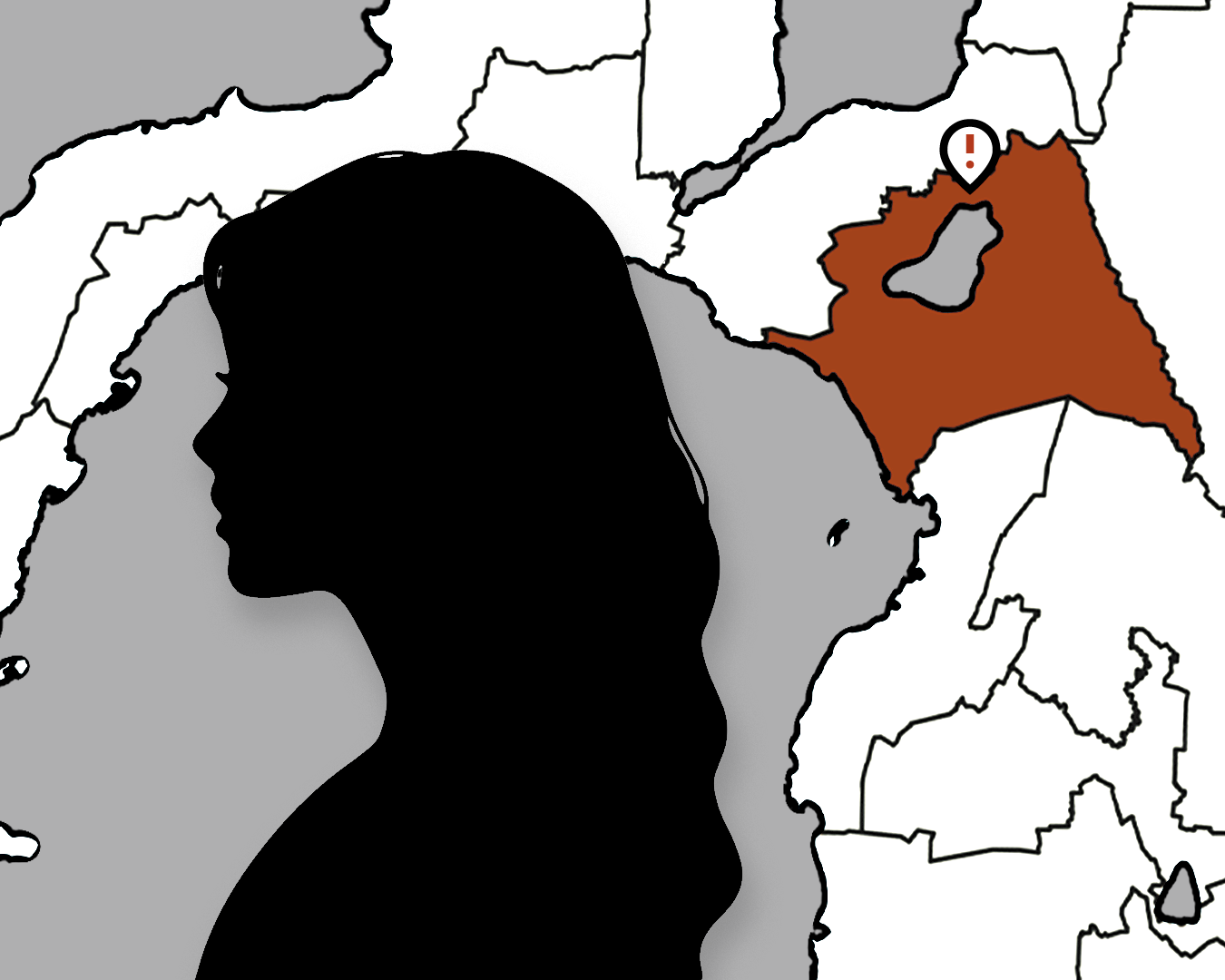

Zaynab, a young Moro, keenly listens as lessons drift across Philippine revolutions and treaties, yet none speak of the land beneath her feet or the arduous struggle that carved her identity.

In a classroom meant to cultivate consciousness, where truths unfold and roots take hold, she finds only silence in the history that defines her people. For thousands of Bangsamoro learners like Zaynab, they often find their own narrative relegated to the margins, mentioned only in passing, if at all.

Against the backdrop of chalk-dusted classrooms and canonical erasures, her resistance stirs. The Bangsamoro narrative persists as a distinct entity of its own—a potent site of resistance, a vessel of reclaiming histories, and envisioning emancipatory futures beyond the confines of imposed identities.

Against Imperial Spoils

Grounded in Islamic beliefs, independence, and resistance to colonial domination, the Bangsamoro have long asserted a distinct identity forged against centuries of foreign subjugation and internal marginalization. Decades of exclusionary discourses and institutional alienation, however, has rendered the Bangsamoro struggle marginalized within the dominant historical imagination.

In textbooks, classrooms, and day to day conversations, Bangsamoro narratives have been systematically obscured in favor of monolithic ideals of Filipino identity.

Historical injustice remains pervasive as it morphs into contemporary forms of co-optation and exclusion, noted by veteran Moro revolutionary and intellectual Salah Jubair in his seminal work “Bangsamoro: A Nation Under Endless Tyranny.” Spanish colonization framed the Moros as an enduring problem—obstinate rebels who defied religious conversion and resisted imperial civilization. This framing perpetuated a divisive historical narrative that sought to alienate the foundational Islamic faith and civilization of the Moros by portraying them as peripheral resistors to an imagined Christian, Hispanized Filipino identity.

Such depiction echoes what theorist Gayatri Spivak refers to as "epistemic violence," wherein the knowledge production process deliberately constructs a narrative that reinforces the ruling order’s imposition. These representations propagate a form of cultural hegemony where the dominant society maneuvers public perception on what is considered legitimate knowledge.

The transition from Spanish to American occupation only worsened the trajectory of marginalization as they ushered in another layer of coercive strategy. Cloaked in the rhetoric of benevolent assimilation, American forces launched brutal pacification campaigns and massacres under the guise of bringing order and modernity to Moro territories. Foreign subjugation endured beyond the battlefields through pedagogical colonialism in the guise of education. Schools and institutions became apparatuses of a regime of memory-making—seeking to overwrite indigenous consciousness and propagate false notions of exploitative development.

As Western legal and moral systems seeped into Philippine politics, structural violence persisted through the illegal annexation of the Bangsamoro homeland. Rooted in colonial historiography, the Philippine state, through its integrationist nation-building agenda, advanced a singular vision of Filipino identity. The facade of national consciousness enforced a state-centric narrative which alienated the Bangsamoro’s religious, sociocultural, economic, and political disposition.

Such narratives persist in literature and schools which mold the foundations and perceptions of the public about the Bangsamoro.

Indigenizing Education

Even as the Bangsamoro continue to resist and assert recognition across various fronts, the distortion of the Bangsamoro narrative remains deeply entrenched within the Philippine education system.

In these learning spaces, structural oppression is perpetuated through the assimilationist and integrationist policies embedded in the curriculum that sustain cultural oppression. Mainstream textbooks rarely offer a substantive account of the long and organized history of the Bangsamoro struggle for self-determination. What little space is granted often reduces decades of struggle into isolated episodes stripped of context and historicization.

The fierce defiance of sultanates against Spanish colonial incursions and the resistance against American pacification campaigns and systematic land dispossession are not given due depth or attention. The failure to accurately and consistently portray the Bangsamoro resistance is both a state tactic and a consequence of the deliberate exclusion of the Bangsamoro narrative from the prevailing historical discourse. Pivotal flashpoints catalyzed by the Jabidah Massacre, which galvanized a triumphant generation of resistance and crystallized the formation of the Moro National Liberation Front, and later the Moro Islamic Liberation Front, are frequently omitted or glossed over.

However excluded, these events serve as crucibles where collective identity and political consciousness ignite and intertwine. But without their rightful place in educational spheres, Moro learners are forced to navigate a pedagogy of invisibility and internalize a narrative disconnected from their roots, values, and identity. In this light, the indigenization of education becomes a non-negotiable pillar in the Bangsamoro’s pursuit of genuine transitional justice and an indispensable tool for epistemic liberation.

Inks of Defiance

An education system that roots knowledge production in indigenous histories, languages, and identities becomes a vital terrain for emancipation. The Bangsamoro Education Code exemplified this commitment for a contextualized learning system that centers the rich and diverse histories of the Bangsamoro within formal education structures. While the Bangsamoro Ministry of Basic, Higher, and Technical Education, and the the Bangsamoro Commission for the Preservation of Cultural Heritage are taking crucial steps towards this vision, structural reforms should be further strengthened to develop a culturally responsive curriculum.

To properly explain decolonial perspectives and nurture critical consciousness among the studentry, teacher-student exchanges must be contextual and reflexive. In the national landscape, Republic Act 10908 (the Integrated History Act of 2016) signals a discursive shift toward pluralism, but its evident lack of implementation reflects the government’s mediocre commitment and political will to making history discussions more diverse and accessible.

But beyond institutional reforms, the true frontlines of liberation in the Bangsamoro lie within the grassroots. The domains once manipulated for distortion evolve into potent arenas of resistance. As the Bangsamoro engages in a transitional juncture, the struggle for self-determination takes on more nuanced forms with literature, pedagogy, and memory-work emerging as sites for reclaiming identity and historical agency. Moro writers, too, have risen to challenge hegemonic narratives and construct alternative futures of peace and justice. The classroom—more than a learning chamber—becomes a battleground for truth.

Amidst impunity and repression, spaces of dissent against state-centric narratives and tokenistic representation becomes a blueprint of liberation. It is a reaffirmation of the legitimacy of the Bangsamoro struggle without co-optation, and where visions of genuine self-determination, beyond institutionalized autonomy, are kept alive for generations. ●